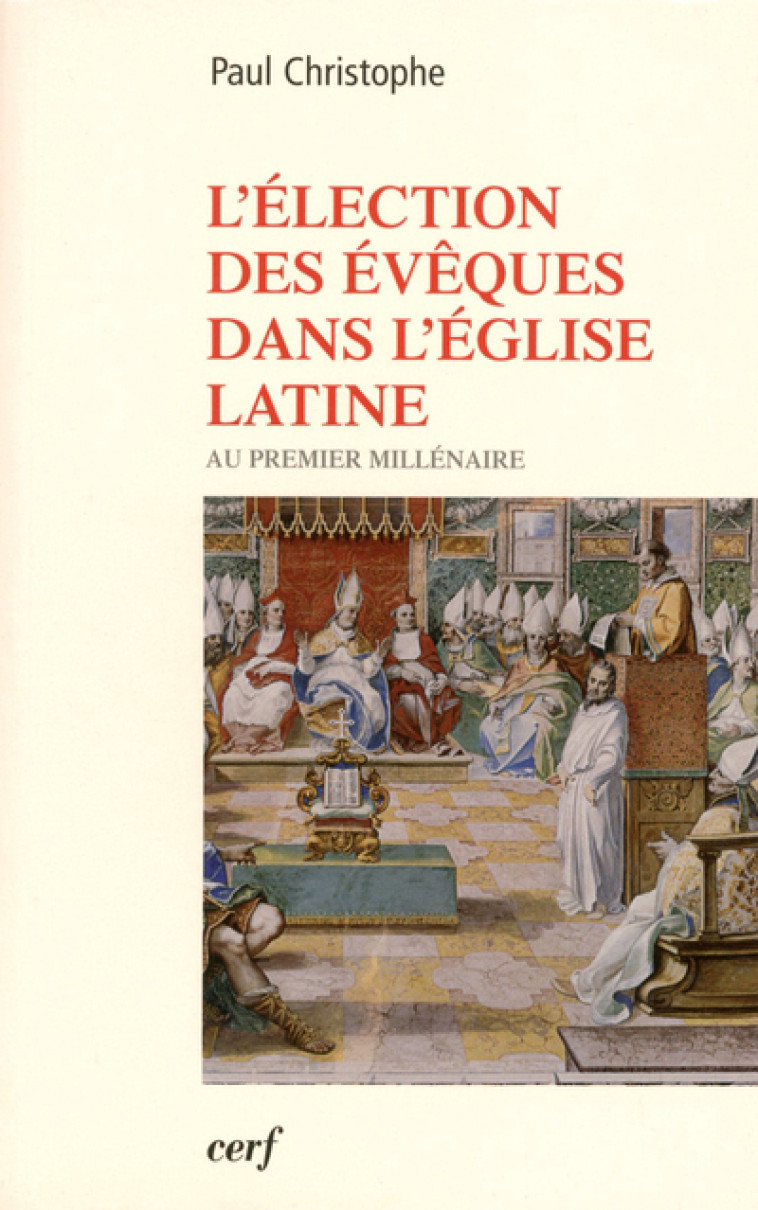

L'élection des évêques dans l'église latine au premier millénaire

Paul christophe

Dans la foulée du concile Vatican II, qui donnait toute sa place à la notion de peuple de Dieu, la participation des laïcs aux responsabilités et aux décisions de l'Église s'est posée au grand jour. Dans beaucoup de diocèses, en Europe comme en Amérique du Nord et du Sud, bien des chrétiens, ordonnés ou non, ont souhaité être associés au choix de leur évêque et ont même réclamé la restauration de son élection par l'Église locale, comme au temps des Pères. Une telle aspiration demandait à être fondée car elle soulevait un certain nombre de questions. D'abord, en quoi consistait cette élection durant les premiers siècles du christianisme ? Est-ce une réalité susceptible d'être à l'origine d'une tradition véritable ? Ou bien a-t-elle coexisté avec d'autres modes de désignation de telle sorte qu'elle ne puisse représenter qu'un archaïsme ? Ou, au contraire, est-elle enracinée authentiquement dans la vie profonde de l'Église à tel point qu'il soit tout à fait légitime de souhaiter sa restauration ? Pour répondre à ces questions, le présent ouvrage envisage la pratique et la législation des Églises latines au long du premier millénaire. Le résultat se révèle étonnant.

--

In the aftermath of the Vatican II Council, which privileged the notion of people of God, the participation of secular members in the Church's responsibilities and decisions became a reality. In many dioceses, in Europe and in North and South America, Christians, ordained or not, wished to be involved in the choice of their bishop. Some even went so far as to demand the restoration of their election by the local Church, as was the practice in the times of the Fathers. Such an aspiration had to be well-founded, for it raised many questions. Firstly, what was the election in those first centuries of Christianity really like? Was it substantial enough to serve as a basis for a true tradition? Or did it in fact co-exist with other modes of designation, in which case it may only represent an example of archaism? Or, on the contrary, was it soundly rooted in the life of the Church to such an extent that its restoration would be justifiable? To answer these questions, this book explores the practice and the legislation of Latin Churches during the first millennium. The result is truly astonishing.